“Oh shit, I have a book”: An interview with Karie Fugett, author of Alive Day

Go buy the book! Right now!

This month I’m trying something a little different. I got the chance to talk with Karie Fugett, whose work I’ve mentioned a lot here in the past—and whose debut memoir, Alive Day, comes out tomorrow—so we did a little pre-release interview. (There are still a few short recommendations at the end of this post, as usual.)

Like I mention later, I first read Karie’s work in 2016, when she applied to the MFA program at Oregon State. It was my first year on the tenure track, my first time fully participating in admissions decisions, so the old impostor syndrome reared its weary head, and I started doubting my own votes. Then I came to Karie’s application, and it was the first time I ever just knew.

I wasn’t the only one who responded that way to her work. Within two years of graduating, she’d published essays in The Washington Post and The New York Times, and had sold her book on proposal to Dial Press, a Random House imprint. Five years later, it’s about to come out. I read the final version earlier this year, and while I’m obviously biased, I meant every word of the blurb I wrote—I wish everyone would read it. If you don’t believe me, just look at some of the early reviews.

If the last two-plus years of admittedly esoteric and uneven (but free!) content here have seemed worth anything to you as a reader, I hope you’ll pay that forward and buy Karie’s book. Preorders and first-week sales matter a lot, and can decide a book’s fate. You can order Alive Day from anywhere you’d like here.

Karie’s back in Alabama now, and it had been a while since we talked, so it was a blast to catch up. I called her last week, and we discussed what it’s like promoting a first book, what it was like writing it, money pressure, writing for normal people, growing up in trailers, working at tourist restaurants, why poor people are funnier, writing from the South, impostor syndrome, being trashy, dumb questions, growing up next to military bases, how class works in the writing world, and more.

I was looking at your social media to prepare for this, and your book-promotion game is kind of amazing. What has it been like to learn that process for the first time, as a debut writer?

It’s not natural for me. There was a learning curve. When I was about a year out from pub date, I just felt like everything was out of my control. I needed something to feel like I had control over, and social media seemed like the most obvious thing. One of the things I wanted to test is what would happen if I made a TikTok a day for a month, and went from there. And my TikTok went from like a thousand followers to over five thousand in a month. I started to figure out the algorithm a little bit. Posting regularly, similar content. I was like, I can do this. So I kept going. Then Trump was elected, and I was like, fuck this. But while I was doing it regularly, what I realized is that you can be a storyteller on any platform, right? Instead of just going on TikTok and being like, “buy my book, buy my book,” it was more like, “let me tell you this story about meeting Stevie Nicks.”

It’s not something I love doing, but I do love my book, and I wanted it to be successful, and that gave me something to have control over. I don’t know if it sold books or not, but it got the story out there to a lot of people.

You’re six days out from pub date as we’re talking. Is your elevator pitch for the book pretty solid at this point?

What if I said no? What if I said I was terrible at those things? I’ve been focusing less on elevator pitches and more on social media content, and getting contacts to send final copies of the book to—contacting anyone I know to see if anyone is interested in just mentioning it. I feel like part of the popularity of a book is just getting its cover on the internet as much as possible. In my case, I feel like people who have discovered it have had really great reactions so far. So I just need people to see that it exists and to have it appear on the internet enough times.

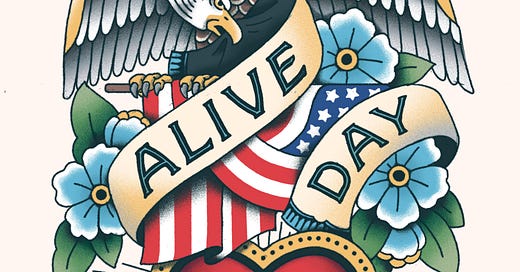

It’s a good book—they should have great reactions. Since you mentioned it, I really like the cover. How do you feel about it?

It depends on the day. I love it today. When I first opened the box, though, I had this … it didn’t feel real, I guess. When I put it on the shelf and saw it across the room next to other books, for some reason my book just didn’t look like other books. I had a panic attack, honestly. But when I opened up the Book of the Month box, that was pretty great. I was like, I like you again.

I remember having this weird feeling (when I first saw my book), where I felt a little disappointed, but also like I couldn’t tell people that.

I think that’s so common. Not just the cover, but all of it. You build the whole experience up in your mind, I think, no matter who you are. And you work so fucking hard. It’s so hard to get anything published at all, no matter if it’s an indie or what, so when that day comes that you’ve just been thinking about for so long … and then it’s just another day, you know what I mean?

I do.

I opened up my books on my floor, in my bedroom, by myself. And I was just sitting there with this box of books. And I’ve been busting my ass to get here. Not just the act of writing, but all the things involved with getting a book published, from school to social media or whatever. And I’m sitting here with this box of books, and I’m like, OK, this is that moment I’ve been waiting for, and it feels like any other moment. It’s exciting, but it’s like, where’s the party?

And then you put it down, and you’re like, I guess I should go make breakfast?

Right.

Last night, I was going back and trying to figure out how long I’ve known about this book. I first saw some pages of it nine years ago. But you’d already been working on it for a few years by then. This book has had a long timeline.

It does have a long timeline. And honestly, very little of that timeline was taken up by actual writing. So much of it was reading other people’s writing, critiquing, learning from people. And a hell of a lot of sitting around thinking and worrying that there’s no way it will ever happen, and just not writing, you know? Trying to convince yourself that it’s possible at all and there’s a point to it. I know some people are like, I just love the journey—

That’s bullshit.

I do, sometimes. But when something's really important to you, and there’s this real possibility of failure, it’s really scary. For two years after I sold the book, I couldn’t write anything. Covid felt so big, and my book felt so small.

There’s a couple things about your book that I think might have made it harder to write than most. One is the story itself, and how important it is to you. If you were writing a novel about a bunch of made-up people, it just doesn’t have the same personal stakes. And the other is that you sold it on proposal, and that’s a pressure cooker.

And when you get the money … obviously you want the money, and we celebrated. But then the day came when I had my editor meeting, and I was getting a deadline, and I was like, wait a second: what if I can’t?

“What if I have to give the money back?!”

There was a point where I’d had (my daughter), and I was like, there is no fucking way I’m ever going to write this book. So I sent (my editor) this depressing email, and she was like, “Girl. You had a baby. There’s a worldwide pandemic. Why don’t you just take two years off?”

That’s an amazingly kind thing for an editor to say.

My editor and my agent are amazingly kind. I got so lucky. They’ve been supportive of all my bullshit, because I am an emotional person, and they’ve never tried to invalidate my experience, or rush me, or try to make me feel small for not being able to do things. They’ve been fantastic.

I’m so glad you wound up in a situation like that.

I know. It’s not like that for everybody.

Reading the final version of the book was a big experience for me in a lot of ways, but one was seeing how much it’s changed and evolved over time. How did you find the final shape, and how did you get there?

I know people say this all the time, but it’s something that I still struggle to let sink in: you have to just allow yourself to write a really shitty draft and not overthink it. Chances are it’s not going to be as shitty as you think, but you need to be OK with the fact that it could be. You just need to get it on paper. That was one of the things I struggled with the most, especially at the beginning. The way I was able to get past that was publishing parts as essays, to sort of kill two birds with one stone and stay motivated. I’d write toward the book, but also thinking, this also has to be a piece that can stand on its own. That way I was producing, and it felt like bite-size chunks and bite-size goals, instead of having to write this entire book that might not get published.

So that’s how it started. And then once I had a piece published in a small lit journal, I was like, “Oh, someone liked it. Maybe someone else will like it enough to buy a whole book of it.”

That’s when I joined the MFA. At that point, though, I was still so afraid of failing to write the whole book that—do you remember me just writing scenes?

Yeah.

It was just a pile of scenes. Rather than thinking, what is this book about, what am I trying to say, I was just thinking instead, what feels important to me? These moments feel big, these feel important. And for me, I like turning memory into scene, I think it’s fun. It’s the in-between, figuring-out-the-big-ideas part that gives me anxiety. So for me it was just trusting my intuition, following these memories that felt important to me, and trying to take the pressure off of understanding the why. For me, I need to just get words on the page.

And then from there I was able to timeline and see a narrative arc. I pulled things out that didn’t seem necessary and put them aside just in case, then started one chapter at a time, sewing these scenes together with commentary and … all that shit in the middle.

The first draft that I turned into my editor was very not in order, time-wise. I think I had it in my head that if I didn’t try to be somewhat experimental, it wasn’t going to be good. I think that was a lot of …

MFA-world stuff?

Yes. A lot of the stuff that made me believe in the first place that I wasn’t the kind of person who ends up being a writer. Because my ideas aren’t exciting enough, or the way I think of things isn’t interesting enough. It’s pretty straightforward for me: something means a lot to me, and I want to write about it. Anyway, I was trying to be fancy, and it was not fucking working.

So I backed up, and had to remember: why am I writing this, and who is my audience? Normal people are who I want to read this. The average person. If I want to fuck around with form or whatever, I’ll do that with something else. This felt like it needed to be more accessible.

So I backed up and made it more linear. And once I did that, it was like, “Oh shit, I have a book.”

That’s so interesting to me, because almost all the books I read don’t seem to be for an average person. But I think you walk this tightrope where you’re writing a book that has a lot of literary craft, and you do a lot of things that are maybe invisible—

I tried to write it well. You don’t see reviewers talking about that shit. And it stings, a little. But it’s fine.

Well, that’s because of what it’s about. With a memoir, they’re always just going to talk about what it’s about.

Exactly.

Because there’s this huge story at the center, right? Cleve, his injury, you know—the thing that’s on the book jacket. But there’s also this idea that it’s almost like an act of translation. You have to translate the world you come from to a lot of people who just can’t even begin to understand: rural poverty, chaotic family, abuse, neglect, high school dropout. I guess the question is just how do you do that, because it seems like such a big thing to have to do.

If I’m being honest, I don’t know if I was really thinking that I had to translate this to people who won’t get it. I was more concerned with trying to access those memories—it’s hard, especially if you’ve experienced trauma. And I was worried that if you have all this black space, it’s going to be hard to pull a book together. So when I was writing this, it really just started there.

But then, once I knew people were going to read it, there were these moments like the one where my mom is pissed that my teacher has a really strong Southern accent. And everyone (outside the South) thinks that everyone in the South just has this really thick accent, and we all understand this language. But I feel like a lot of people don’t understand the diversity in the South. So that scene felt important to me, even though it’s small, for that reason. I was thinking about what’s in the South, like pecan trees and cicadas and those sort of things, and trying to incorporate them somehow.

I feel like one of the things people are not going to understand about your book until they read it is that it’s really funny in some parts. I know that sounds weird—clearly the story’s not funny—but there are a lot of funny things I recognized, whether it’s living in trailers or parents selling Amway or working at tourist restaurants. And it seems like Cleve was a really funny guy, too, based on some of the things he does and says. How do you make a story that’s tragic, and huge, and has so much to say about our country—but also make it funny in parts?

Natural-born talent.

Fair enough.

I’m kidding. But part of it really is that my voice just sort of comes out. A lot of that stuff, if you’re true to yourself and your own voice and write it without worrying so much about sounding a certain way or being a certain thing, your own personality starts to come out, and usually in a positive way. I have a dark sense of humor, and I knew that I wanted there to be humor in it. So I’d have these dark thoughts and just think, “I’m going to fucking put that in and see what happens.” So maybe that’s the process. I found that I had a knack for weaving in moments of dark humor.

My theory is that that’s a class thing. Poor people are funnier. I think you have to be, to survive all that shit.

Right! Because you’re going through all this shit and you can be completely miserable, or you’ve got to figure out how to make fun of your surroundings a little bit more.

Yeah, that’s one of those things that doesn’t really translate to literaryland. Sometimes you wind up making dark jokes and then people just have this horrified look on their face.

OSU was great, but when I got there I did still feel a little rough around the edges. And I was nervous to let my personality come out a little bit. Because when I do, I’m not, like, a classy person. I can pretend, but for the most part, I’m a little trashy. That’s my most comfortable self.

And it’s hard to own that. Especially when you’re younger and you’re in this new place. So there was probably a little code-switching, or just being silent and hoping nobody will notice you. The more I wrote, though, the more I started leaning into it. I also started to realize that the authors that I like and the stories that I like, that’s the thing I like about them. They’re unique, they’re themselves. They don’t give a shit what other people think. So I was like, you know what? I can be a little trashy, and also from the South, and be a writer. And that’s fine.

Amen! Are there any questions you hope people will ask about this book? Or that you hope people won’t ask?

The other day, someone asked a terrible question. They were like, this book seemed like it must have been really difficult for you to write—you write about a lot of traumatic stuff. How did you get through all of that in order to write this? And I was thinking, how does anyone get through trauma? I don’t fucking know. It’s either that or die. You just do it. Good intentions—don’t get me wrong. But I just didn’t understand the question. You’re definitely not thinking about it the whole time. It’s usually kind of panicky, you don’t have a lot of great options, and then you either get lucky or you don’t.

One of the epigraphs points to that, right? You don’t have options—you just have to survive. I also loved that other epigraph, from Sartre: “When the rich wage war, it’s the poor who die.” That made me think you might have some thoughts on the role of class in your book.

For sure. As I was writing it, I had a few readers say the beginning doesn’t fit. There was a lot of debate about the beginning, because it jumps from that scene where I find the gun under my pillow, pretty far back into childhood—it has a pretty long timeline for a memoir. There was some debate about whether the childhood stuff was needed. The reason I wanted it there, personally, is because one of the goals was not just to say people go to war and get wounded. It was to say who goes to war and gets wounded, and who doesn’t, and why.

As I was writing it, and doing op-eds, I started to learn more about not just my experience, but how the military-industrial complex works. And how there are people who actually make money off of war, which is to say off the backs of people like my husband. And I kind of knew that before, but again, I was a high school dropout. Then I went to school for writing. So I’m still catching up on things I should have known a long time ago. And one of them is having a better understanding of how the military works, how our country works. I think the way our country is set up is purposeful, that they want people to be fighting each other for resources, they want them to be sick, they want them to be poor—not all of them, but enough that they have a constant flow of cannon fodder.

And that doesn’t mean nobody joins the military out of a sense of patriotism. There absolutely are people who do that. But if you look at where recruiters go, it’s not rich, white communities. It’s usually really poor, often Southern, or around military bases—because they know, statistically, if they have family in the military they’re more likely to serve. They’ve got these recruiters at their doors, they’re leaving voicemails. Some of these schools are even making it seem like the ASVAB (the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, a test given to prospective recruits) is required.

My high school did that.

I have a friend that happened to. She went to a predominantly Black school outside Mobile, and she said, “I thought I had to take it.”

I remember (at my rural, working-class high school near a military base in Arizona in the 1990s) nobody encouraged us to take the SAT, we didn’t have to take the PSAT. But we did have to take the ASVAB. And then our career day, my senior year, was recruiters for every branch of the military, a plumber, and one guy from a community college.

That sounds about like ours. And I didn’t know this wasn’t normal. I just thought this is how schools were.

Same.

And then when I realized that’s not everyone’s reality, I was like, holy shit. And suddenly, my new purpose for the book was like, I want to show those people who’s fighting their fucking wars for them.

Because one of the things that upsets me, too, is that I don’t like war. I want peace, and to spread the wealth, and for everyone to be happy. But that’s not our reality. The reality is that all of us live in a country that benefits from these wars. It doesn’t matter who you are. Just being here, and a citizen, you are a part of that, and you can’t just look away. I mean, you can, but that doesn’t mean you’re not complicit. And there are entire groups of people who are just like, “those are the people who fight the wars.” And then they just don’t think about it.

So I thought, how can I illustrate that these are human beings. They’re not just born wanting to go kill people. There are reasons people join the military, especially during wartime. And it’s often because they just want a house, or a job, or to get their mom out of poverty. I just don’t think people think about it that way.

Our mutual friend, the writer Matt Young, talks about this in his work: how stark that divide is between the military and civilian worlds now.

Yeah. And then there’s an even further divide, depending how wealthy someone is, and where they come from. Because they don’t even see military bases sometimes. It’s not a part of their lives at all.

That was one of the things I didn’t realize until I moved to San Francisco in my mid-20s. My whole life until then, I had lived next to a major military installation. And then I was like, where’s the Army or Air Force base?

Same. And I don’t think it really clicked with me until I was doing all this research. I just never thought about it before, but as I was researching I was trying so hard to imagine this life where these people never think about the military at all. They don’t see the bases, they don’t see crew cuts everywhere, they don’t have to worry about their sons getting shipped off, they don’t have to deal with recruiters. And that blew my mind a little bit. I still kind of don’t get it.

Besides buying the book, where should people find you online?

Instagram is good, and also my Substack. I’m trying to grow that. Substack’s probably the best place, long-term. According to publishers, the bigger the Substack, the better, if you’re trying to sell a book. So tell your students.

I will! They might be curious to hear that. A lot of them are navigating this question of, how do I promote my work?

It’s a weird space. I think most of it is just paying attention and being flexible. And some people have that savviness and some people don’t. And you can hire people, but it’s expensive.

That’s one of those class things that pisses me off the most—that like ten years ago, the whole publishing industry decided that if you have the money, you can pay $50K or more to one of those publicity firms in New York, and you’re just paying to have a bestseller.

Yeah, I was like, “Hell no.” It just seems insane to me.

I’ll let you go, but last thing: we really want to bring you out to OSU in the Fall, so keep an eye out for an email about that. And don’t forget about me when you’re famous next week.

#

A few quick recommendations:

• A certain special somebody published a lil’ love poem in The Atlantic.

• Big fan of Lucy Sante’s work—Low Life is a buzzsaw of a book—and I’ve been liking her Substack, especially this recent post about being labeled a memoirist and the idea of specializing.

• Never expected to recommend a TED talk, but this one distills pretty much everything I’ve been thinking lately about online media and AI.

• Also unexpected: this month, thanks to a random Spotify suggestion, I discovered that Yoko Ono kinda rips?

Great interview and the book sounds amazing. I am going to get a copy from the Indie bookstore where I work!

I love this interview! I preordered Alive Day, and I can’t wait to read Fugett’s work (btw, my initial impression of the cover was that I loved it—though I am a bit biased towards heart shapes and sailor tat designs).

Also, I appreciate the conversation about accessibility and audience: “Normal people are who I want to read this.” And it’s frustrating that a more accessible memoir isn’t always appreciated for its craft, when it absolutely should be!